Unshaming Shame: Part 1

Photo Credit: Adrienne Rich

When I was in 6th grade, I liked a boy in my class: his name was Sean. I thought he was amazing, handsome, and I had proverbial stars in my eyes as I gazed at him in class. He was one of the popular kids. I was not.

One day, he came up and talked to me. He was kind, and my affection was cemented. He asked if he could call me after school. I said yes. I felt complete, like everything was okay, just imagining Sean liked me the way I liked him. I felt seen for one of the first times in my life. I had never quite fit in with groups in school; I had friends, but was always on the fringe. I had trouble standing up for myself. I was the bookworm, with crazy red curls and freckles, the kind of nerdy girl who was quiet and kept to herself, more comfortable outside in the woods by my house than with groups. I just wanted to fit in.

I went home that afternoon and waited by the phone. My mom was busy in a different part of the house, so she wasn’t around. When the phone rang, and I answered to Sean on the other end of the line, my heart was in my throat. We talked and laughed, and he asked me to “go with him.” I, of course, said yes.

I was walking in the clouds. This would change everything.

The next day at school he ignored me. I didn’t understand why or what had happened. After class, he left with his best friend, raucous laughter in their wake when they walked by me, as I sat frozen at my desk. The best friend came back in while Sean waited, watching from the hallway, and said to me as I was sitting at my desk still, “What… did you actually think he would like a freak like you?”

I was heartbroken and intense emotion rose up; my face turned scarlet, my hands sweaty and shaking. I didn’t know at the time of course, what I was feeling was shame.

As a child growing up in my family, there are not a lot of memories that aren’t colored by the stain of toxic shame. Countless times as a little one, I would try to please my parents and then “do it wrong,” afterward being berated and criticized, which more often than not ended in physical abuse and/or being locked away in my room for days at a time. These events were just everyday occurrences; it was my normal. This taught me early on that my mother was perfect, I was completely flawed, and I could never do things “right.” It paved the way for toxic, pervasive shame, manifesting as perfectionism, imposter syndrome and a whole host of other behaviors designed to keep me small, silent, abiding and unseen as anything that didn’t fit with what was ‘normal.’

As a human, I would have started out with the protective emotion of healthy shame, but it turned quickly toxic. At the time of course, I had no idea of the power of this mysterious emotion; all I knew was I was never good enough. The physical and emotional abuse from my family solidified that I was inherently flawed, ugly, and lacking.

I carried this toxic shame into adulthood; of course there’s no way to avoid it, even though the logical part of the brain knows, I’m safe now, it’s not happening that way anymore. How does this mysterious emotion affect us so deeply that it withstands decades of healing, and then still pops up to protect us and sends us into the dreaded shame spiral?

What is Shame?

Shame is a social construct emotion. Shame informs us of an internal state of inadequacy, unworthiness, disconnection, regret, or dishonor. Everyone has healthy, normal shame, it is one of the core emotions human beings experience. Feelings are the mental labels we assign to the embodied sensations of emotions, and they are always colored by our perception. Emotions have both mental and physiological components. Since shame is an emotion, not a feeling, it is like raw data, messengers, signals from the body to the brain, it’s what happens in the body that tells me how I’m feeling.

It’s a natural, human emotion, but we can be unaware of its value. Shame is the great protector.

We are born with the biological need for survival, which means we must be accepted by our family and community. There is fear underneath shame that says, “If I am shunned by said family, or community, I won’t survive. If I’m a liability, not an asset to my group, or I have done something ‘bad,’ my Littles (inner child) and (other?)parts fear for my safety, as I cannot take care of myself.” The main reason we have the emotion of shame is to protect us from being shunned or exiled by those we need to care for us and keep us safe.

How beautiful, sad, and powerful that is. The essence of developmental trauma and shame turned toxic, is a cloak of pain which constantly tells us we aren’t good enough, we’re defective, so why should we even try. It’s a self-defeating mantra which penetrates our adult relationships. Shame is the most misunderstood emotion; people shy away from looking at it and discussing it, because it’s so painful.

Shame happens in the absence of kindness. In the deepest parts of ourselves, we work to untangle the messages of shame and love, while struggling to make meaning. So much of the time, we don’t have language to define shame without shaming ourselves even more.

We grieve, not only the childhood we didn’t have, but the adulthood we didn’t have, as a result of the past. Our emotions are gently relentless, and to dance with them without delving into shame is the crux of our internal work, to grieve what happened in childhood, to embrace the loneliness, which can bring wisdom, and to touch on the anger which can safely help us to release the shame.

Shame is the emotion that immediately makes us want to deny or hide what we are doing, feeling or our behaviors, because if another person found out about it, they would shun and reject us, and as a result, we wouldn’t survive. I’m five years old and I can’t go out and get a roof over my head or food to nourish me. I’m entirely dependent on my caregivers.

Shame is a primary emotion and a nervous system freeze. (Bret Lyon, co-founder and co-director of the Center for Healing Shame) The emotion of shame causes activation in the sympathetic nervous system, causing a fight/flight/freeze/fawn reaction. We feel exposed and want to hide or react with anger, while feeling completely disconnected from others and anything we potentially view as positive within ourselves. We may not be able to express ourselves as we wish, and we may be consumed with self-loathing, which is made worse because we’re unable to escape the tidal wave of emotion that says “see, you aren’t good enough,” or “who do you think you are.” Our shame story continues from childhood into adulthood, unconsciously.

Human beings are biologically hard-wired for connection to others and if we are shamed, we can risk disconnection at the core level of survival and our need to be accepted. We all have our own sensitivities or pockets of fear that produce the emotion of shame.

The intensity of a shame experience varies depending upon life experiences, cultural beliefs, environment, personality, trauma history and the circumstances of the situation. Anything that breaks connection causes a shame response.

Shame is an emotion that people have a difficult time defining. In her book, I Thought It Was Just Me (But It Isn’t,) Brené Brown defines it in depth, based on the research:

•Shame is that feeling in the pit of your stomach that is dark and hurts like hell. You can’t talk about it and can’t articulate how bad it feels because then everyone would know your ‘dirty little secret.’

•Shame is being rejected.

•You work hard to show the world what it wants to see. Shame happens when your mask is pulled off and the unlikeable parts of you are seen. It feels unbearable to be seen.

•Shame is feeling like an outsider- not belonging.

•Shame is hating yourself and understanding why other people hate you too.

•Strong potential for self-loathing.

•Shame is like a prison. But a prison that you deserve to be in because something is wrong with you.

•Shame is being exposed- the flawed parts of yourself that you want to hide from everyone are revealed.

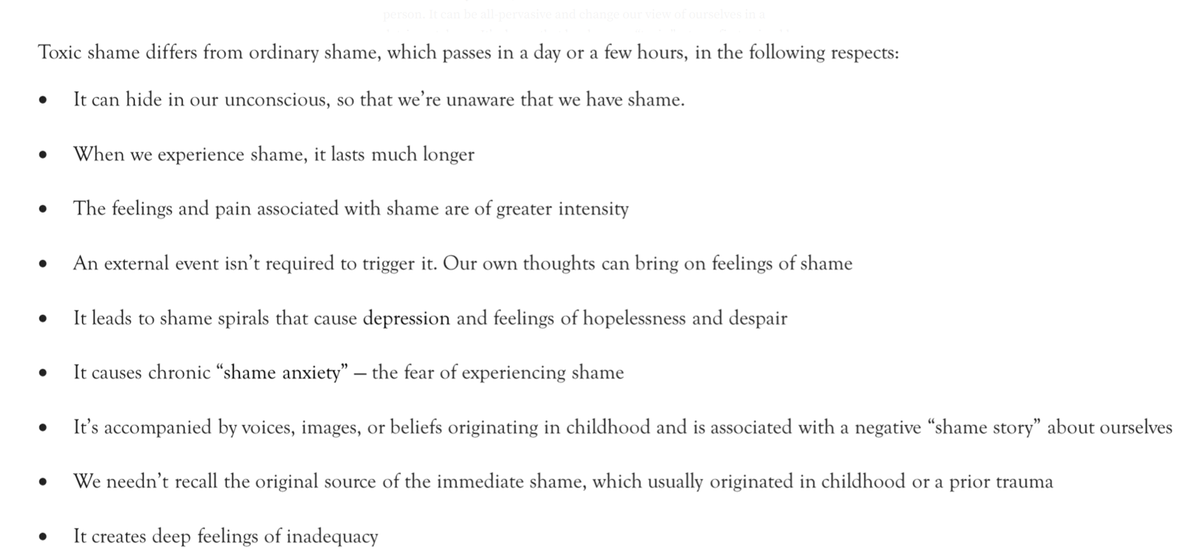

Toxic Shame

Unlike ordinary shame, toxic shame becomes internalized within the person. It can be all-pervasive and change our view of ourselves in a detrimental way. It’s shame that has become “toxic,” a term first coined by psychologist Sylvan Tomkins in the early 1960s in his study of human affect. For some people, toxic shame can take over their personality, while for others, it lies beneath the surface, but decisions, feelings, and actions are all impacted by it and it can easily be accessed in everyday circumstances.

The experience of shame is inevitable for any human being insofar as desire outruns fulfillment. The essential condition for the activation of shame is “I want, but . . .” (Silvan Thompkins, Exploring Affect p.406)

So what does all this mean, in the context of developmental trauma? Shame, as the great protector, rises up in an attempt to keep us safe, because if we’re small and silent, we won’t try and risk getting hurt again.

Within the characteristics of toxic shame, and the pervasive nature of it and because it’s been internalized, we feel like we are our shame. Toxic shame becomes the reality. It feels like it’s part of our personality, and colors everything we do and see; it changes how we make meaning in terms of what does this situation or how I’m being treated, say about me.

This leads to toxic, shame-based beliefs about ourselves. The fundamental belief underlying shame is that I’m unlovable — not worthy of connection, not good enough. It can include beliefs such as:

• I’m stupid

• I’m unattractive (especially to a romantic partner)

• I’m a failure

• I’m a bad person

• I’m a fraud or a phony (Imposter Syndrome)

• I’m selfish

• I’m not enough (this belief can be applied to numerous areas)

• I hate myself

• I don’t matter

• I’m defective or inadequate

• I shouldn’t have been born

• I’m unlovable

•I’m too…<fill in the blank>

•I’m flawed, defective, it’s my fault, I’m responsible…

•I’m not…<fill in the blank>

Lots of variations on the above! From our trauma, we see the world and ourselves through a lens of shame constantly.

I work with a lot of people who have navigated their attachment wounding, abandonment issues, and childhood complex trauma. And yet I hear from clients and students all the time about how they still view themselves as not good enough, as flawed, as defective, and to blame when things don’t go “right;” and then there’s the whole, what-did-I-expect: this is me we are talking about. So why do they still view themselves this way, after years and sometimes decades of internal, hard work?

You guessed it: this is the toxic shame piece. The effects of having long-term toxic shame are huge: we can catapult down a shame spiral in a heartbeat. And because shame is a primary emotion and a nervous system freeze state, we feel activated, are triggered, and basically feel like rubbish about ourselves.

‘Toxic shame can obliterate your self-esteem in the blink of an eye. In an emotional flashback (trauma response) you can regress instantly into feeling and thinking that you are as worthless and contemptible as your family perceived you. When you are stranded in a flashback, toxic shame devolves into the intensely painful alienation of the abandonment mélange — a roiling morass of shame, fear, and depression. The abandonment mélange is the fear and toxic shame that surrounds and interacts with the abandonment depression. The abandonment depression is the deadened feeling of helplessness and hopelessness that afflicts traumatized children.’ (Complex PTSD: From Surviving to Thriving, Pete Walker, page 5)

So much to navigate! Starting to untangle our toxic, pervasive shame is an enormous part of healing from developmental trauma. In Parts 2 & 3 of this series, I will go in depth on exploring, learning to navigate this powerful, mysterious emotion consciously, what shame reactions are and how they work, shame binds, healthy shame and how to counter-shame within the context of awareness, acceptance, and action, to slowly untangle and loosen the grip of toxic shame in our healing from developmental trauma.

When I think back to the shaming experiences in my life, including the crush in junior high school and what played out, I see again and again the need for us to look a little closer at our internalized toxic shame. We can transform it into healthy shame and it’s amazing capacity to keep us safe in our healing journey is stunning, but each of those painful experiences can feel like a thousand splinters under the skin.

Today, please take care of yourself and if you are struggling, reach out to someone safe. Shame hides in secrecy, when we can hold it up to the light, it dissipates and connection with other safe human beings is key.